Forgotten Heritage of Georgian Catholics

Levan Sutidze, religious commentator of Tabula

One hundred years ago, after a long interval of 106 years, Kyrion II, within several weeks of his election as Catholicos Patriarch of the Georgian Church, sent the 15th letter to Pope Benedict, the head of the Catholic Church. A century later, that letter has gained an utmost importance for Georgian Catholics.

To respond to numerous challenges, Georgian citizens of Catholic faith have to emphasize their contribution to, and the role in, the history of the country. However, the best illustration of this contribution is the letter of Patriarch Kyrion II whom the Georgian Church canonized as a saint. In the letter, Kyrion recognized a special role of Georgian Catholics in the history of Georgia since the 13th century. He referred to Catholic missionaries as “kind shepherds,” “healers of bodies,” “providers of education and knowledge,” not as “spiritual expansionists” or “debasers of Georgian gene.” At the end of the letter, the Patriarch even made a vow: “On the day of restoration and of happiness of the Georgian Church, bearing in mind our past, I send my best regards to your holiness and pledge that followers of your Church will not be persecuted by me or the Georgian nation. I hope that Your Holiness will not neglect Georgian Catholics and their numerous religious and civil needs.”

The aim pursued by Father Michel Tamarashvili, a Georgian Catholic and prominent public figure, in writing his famous work “History of Catholicism among Georgians” was to put an end to anyone’s attempt to deny Catholicism of Georgians. The book contains various historical sources, correspondence of Georgian kings or nobility with the Pope of Rome. To stop the denial of Catholicism of Georgians once and for all.

The history of Catholic Church in Georgia traces back to the 13th century. According to researchers, it was in that period, i.e. after two centuries of so called East-West Schism (1054), when a disagreement occurred between the Georgian Church and the Roman Catholic Church. Despite the split, Georgian kings received Pope’s representatives of various orders with dignity and respect. The first to arrive in Georgia were Franciscans[1], soon followed by Dominicans[2]. A Catholic monastery was established in Tbilisi. There was a Latin episcopal see in Georgia from 13th century to the beginning of 16th century, which was run by 12 bishops at various times.

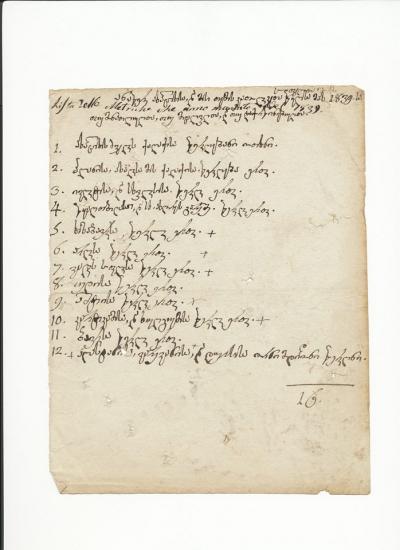

A list of baptized, married and deceased members of the Catholic community. Akhaltsikhe, 1839.

Throughout the history of Georgia, save rarest exceptions, Catholic missionaries or Georgian Catholics always enjoyed the support from Georgian kings. They were represented at the king’s courts, engaged in spreading literacy, establishing educational or healing centers. Catholic missionaries left an invaluable information for the research of Georgia’s past.

In 1861, Georgian Catholics founded a brotherhood of Congregation of Immaculate Conception in Istanbul, which existed till 1974. Established by Father Petre Kharischirashvili, this Catholic monastery helped Georgians obtain European education; it was this educational institution that raised Catholic priests: Father Michel Tamarashvili, Father Ioane Gvaramadze, Father Mikheil Tarkhnishvili and others who were respected researchers of the Georgian Orthodox Church and active members of the national liberation movement.

There was an active cooperation between the Georgian Orthodox autocephalic clergy and the Georgian Catholic clergy. Georgian Catholics advocated the restoration of autocephaly of the Georgian Church and supported Georgian autocephalic bishops who were persecuted by Russia. For their part, the hierarchy of Georgian Orthodox Church actively supported Catholics in their desire to restore Catholic episcopal see; in 1917, a meeting of Georgian Catholics was attended by three Georgian bishops including locus tenens of Catholicos-Patriarch (future Patriarch) Leonide Okropiridze.

Georgian Catholics had prominent representatives: Zakaria Paliashvili, who composed the music for Georgia’s hymn and founded the national school of composers, was born to the family of Catholics; a founder of Tbilisi State University, Petre Melikishvili, was a Catholic too. Other prominent Georgian Catholics included Simon Kaukhchishvili, a founder of Georgian classical philology; Petre Otskheli, a Georgian set and costume designer and founder of Georgian modernism, and many others who made an invaluable contribution to the development of the Georgian culture and science. Still very little is known to Georgian society about the activity of Georgian Catholic businessmen and philanthropists, brothers Zubalashvili.

The followers of the Bishop of Rome try to showcase the Catholic cultural heritage in Georgia even today. First, they named an official church publication, and then the university, after a prominent Catholic public figure Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, therewith countering the attempts to distort the history.

Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani was one of the greatest writers, scholars and politicians in the history of Georgia. His writings prove his genuine Catholic belief, in which he repeatedly and openly recognized the Pope as the shepherd of the church and the Catholic teaching as a correct creed – orthodoxy.

“Georgian episcopes and clergy were unhappy about my travel to Rome… They kicked up a storm about it; called a meeting to condemn me. But they failed to involve the king. He ruled three more months and then King Bakar ascended the throne… He was deceived. They forced Mtskheta to forget my affection and service, held a meeting and demanded that I condemn the Pope; I did not deny the orthodoxy. They wanted to inflict much evil, but the God protected us from all ills. The King treated us with honor and their evil deeds were thwarted. When King Vakhtang learned about that, he got angry and reprimanded everyone,” Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani wrote.

Catholics Today – Discrimination and Indifference of the State

After the Sovietization, Georgia started to persecute the Catholic Church. Catholic churches were closed down; the apostolic administrator, Father Shio Batmanishvili, was sent to exile and executed there. Despite the persecution, the Georgian Orthodox and Catholic Churches maintained cordial relations in the Soviet period. The situation, however, changed radically after Georgia had regained the independence.

In historical region of Meskheti, where Catholics have lived in compact settlements, Georgian Catholics face numerous problems to date: children of Catholic faith often experience discrimination in public schools; Catholics face problems at places of employment and in public entities; they are often offended verbally. The state is largely indifferent to problems of Catholics. For quite a long time now Catholics have encountered problems in obtaining a construction permit and registering a land for the construction of a religious building.

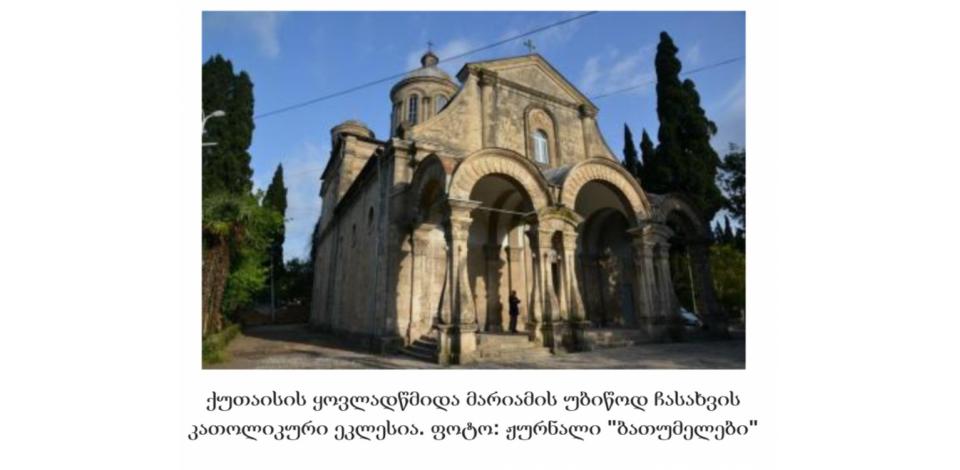

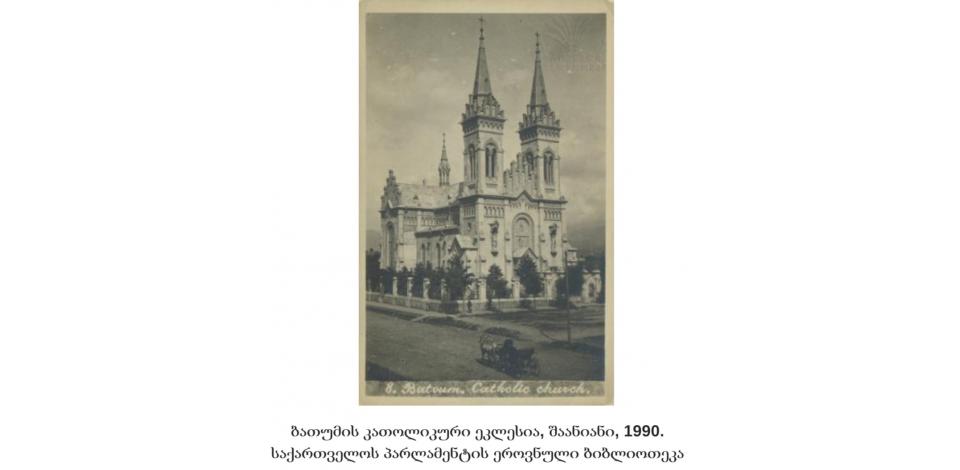

The restitution of historical property seized during the Soviet period is an especially painful issue for Catholics. During years the Catholic community has asked for the return of five churches which were seized during the Soviet rule and then, in the 1990s, transferred to the Georgian Patriarchate. These buildings, referred to as disputed churches, stand in Kutaisi, Gori, Batumi and Ivlita. Meanwhile, their appearance have been changed: iconostases have been erected and a substantial part of frescoes has been erased. Inscriptions proving the Catholic origin of the churches have also been partially destroyed.

The construction of Batumi cathedral of neo-Gothic style, with three domes, started in 1897. The construction was financed by Georgian Catholic businessman and philanthropist Stepane Zubalashvili. In 1903, Episcope Ropp sanctified it. Bells adorned with Georgian inscriptions were a gift from Italian Catholics. After a century of its construction, parts of Catholic frescoes were damaged and an iconostasis was erected. In 1989, under a decision of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, the Batumi Catholic Church of Blessed Virgin Mary was transferred into the ownership of Georgian Patriarchate.

A church in the village of Ude, in the Adigeni district where the majority of population is Catholic, shared the same fate. The church was built between 1904 and 1906. An inscription on it is a proof of not only Catholic origin of the church but also of a long tradition of tolerance among local residents: “2120 Catholics and 520 Muslims, who are Georgians by origin, built this church in Ude. We dedicate our work to you, Virgin Mary.” After regaining the independence, Catholics in Ude cannot pray in the church which was built by their ancestors. The appearance of this church has also been changed.

The situation is similar in other churches too. For example, a Kutaisi Catholic Cathedral was built on a location which King Solomon II transferred to Catholic priests by the deed of gift in 1800: “With the will and help of God I made up this deed of gift… for our dedicated priests… we give a land … next to your church… for your priests in a permanent possession… and if anyone - be they a clergy or layman… infringes on this gift… be they punished severely by God … and cursed for eternal hell…” (An excerpt from the Deed of Gift of King Solomon and Queen Mariam).

The construction of the church began in the 19th century; however, since Catholics were persecuted in the Russian Empire, it lasted until 1862. In 1989, the Catholic congregation was no longer able to conduct religious service there; a Catholic organ was lost too. The appearance of this church has been transformed too.

The Catholic Church made an attempt to reclaim the Kutaisi church through the government. Toward this end, the Catholic congregation of the Western Georgia established an association Savardi in 2000. A year later, the association filed a complaint with the Tbilisi district court. The court did not satisfy the complaint on the ground that the disputed church was transferred to the Orthodox Church in 1990s and that under the 2002 constitutional agreement (Paragraph 1 of Article 7[3]), it was the property of the Patriarchate. Moreover, the court concluded that the association Savardi was not a successor of the Georgian Catholic Church. Catholics appealed the decision in the Supreme Court of Georgia.

The Supreme Court upheld the decision of the lower court. It disregarded a letter of Giuseppe Pasotto, the apostolic administrator of the Catholic Church in the Caucasus, certifying that Savardi was the only successor of the religious association of Catholics that operated in the past and was recognized by the Pope of Rome.

Moreover, the Supreme Court considered that at the time of dispute, the church was Orthodox because in 1989, the Council for Religious Affairs of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union transferred it to the society of Orthodox believers. According to the decision of the Supreme Court, administrative acts of the Council were not abolished and therefore “remained in force.”

Thus, the Court failed to restore historical justice and defend constitutional rights of the Catholic community.

After years of struggle, the Catholic Church has chosen a moderate form of relationship with the state and the Orthodox Church. Catholics do not demand an immediate return of churches or the removal of Orthodox Christians from there. The nature of their demand is more principled than practical – as the Catholic Church declares, they will see no problem in the conduct of service by Orthodox Christians in the church provided that the interests of the two denominations are accommodated.

Unfortunately, religious diversity of Georgia is often regarded as a threat than a wealth today. Society is ignorant of the contribution of various denominations, including Catholics, to the country’s past or present. This is further aggravated by myths about “western spiritual expansion.” Catholics are often called “Papists” who primarily pursue the interests of a foreign country. Catholics have to assert that they are Georgians, citizens of Georgia, not “French.”

Charity of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church provides social service and carries out a charitable activity. A charity foundation Caritas Georgia, founded by the Church, has operated in Georgia since 1994. This foundation provides assistance to various social groups.

Caritas implements healthcare and social programs, providing primary health care, homecare, vocational development services to socially vulnerable citizens. Caritas assists up to 1,000 children and youth annually. It operates day canters, family-type homes and night shelters for children living and working in the street/deprived of care operate in Tbilisi, the Arali village, the town of Vale and the city of Rustavi.

Every day, a soup kitchen serves hot dinner to some 600 individuals representing socially vulnerable, living below a poverty line, multi-children families, internally displaced persons and persons with disabilities. A mobile medical group provides medical consultations, check-ups and necessary medication to socially vulnerable population in Tianeti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Kakheti regions.

Since 1995, the first aid medical center in Kutaisi renders service to some 100 socially vulnerable persons every month.

Since 2003, a shelter Dormitory has been open to homeless people for a night stay. The shelter accommodates up to 30 persons every night.

Since 2005, the project House of Hope assists alcohol dependent persons in their rehabilitation. Also, a social center of Mother Teresa’s sisters shelters dozens of citizens in Tbilisi.

Since 1993-1994 to date, with the assistance of other partners, Caritas Georgia has provided humanitarian aid to victims affected by various disasters having happened in Georgia (war, financial crisis, floods, earthquake, et cetera).

Few may know that the Catholics have even built an Orthodox Christian church for Orthodox Christian beneficiaries of the Caritas Georgia.

This is an incomplete list of those charitable and social projects which the Caritas foundation and the Catholic Church of Georgia have implemented in Georgia during years. Since 1998, a clinic of Order of St Camillus has operated in Tbilisi, providing free treatment to homeless people; there is also a Camillians’ center for persons with disabilities.

In 2016, being on a visit to Georgia, Pope Francis visited Camillians’ medical center with an absolute majority of beneficiaries being Orthodox Christians. When an Orthodox Christian passes away, Camillians invite an Orthodox priest for the funeral service – the charity here is totally free from proselytism and religious teaching.

This article was made possible by the generous support of the American People through The United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content of this article is the responsibility of TDI and the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of East West Management Institute, USAID or United States Government.

The project is implemented by the Tolerance and Diversity Institute within the framework of USAID program, Promoting Rule of Law in Georgia (PROLoG), carried out by the East-West Management Institute (EWMI).