Diversity in the Medieval Georgian Literature

Author: Nikoloz Aleksidze

When thinking about literary or, in general, cultural diversity, the Middle Ages is, perhaps, not the epoch that would first come to mind. Rather, our perception of that long and eclectic period is that of the era of closed-minded monks who confined themselves to monasteries and tediously rewrote one and the same texts, memorized one and the same ideas, created one and the same icons and images. As if nothing original had been created until the dawn of the Italian Renaissance that ignited the creativity across almost entire Europe.

Indeed, diversity, originality, difference and even more so, tolerance did not yet exist as notions in the Middle Ages. Anything novel or different was considered suspicious and even dangerous whereas loyalty to tradition was viewed as desirable. However, that was true only nominally and, so to speak, conceptually. Perhaps, it was precisely owing to the absence of the notion that diversity, as a subject of defense or rejection, did not exist as a problem. Medieval cultures, both western and eastern, were somewhat unconsciously permeated with diversity. Ideas, images and symbols of literature, art, philosophy or theology traveled through and merged with neighboring or remote cultures so smoothly that rarely would a question arise about the origin of this or that phenomenon - whether it was foreign or native, local or imported.

Therefore, openness, a sort of humbleness to something greater and more magnificent was a dignity in the Middle Ages to a larger extent than in the Classical Age. As Rémi Brague, a French historian of medieval thought writes, everything in the Middle Ages was engaged in an endless cycle of exchange between nations. An anecdote from the 9th century Arabic encyclopedia charmingly reflects that process: a Greek who found himself among representatives of other ethnicities started to boast about his nation’s scientific achievements. He was instantly reminded that the Greek borrowed their sciences from Persians and many other peoples. He also agreed jovially and said that nothing had been invented by one people but all peoples had been always giving and receiving.

The Mediterranean Basin was this sort of a melting pot of cultures. Since the period of late antiquity, it was a place where languages, cultures, religions and civilizations met and melted into a hybrid product. Roman, Arab, Syrian, Persian, Christian, Muslim, Hebrew travelers, traders and pilgrims met one another on board the ships, beaches and islands, in marketplaces of Damascus, Alexandria, Constantinople, Baghdad or Tbilisi, exchanging goods and with it, stories and ideas. In that epoch, when faith and intolerance made almost impossible to establish a dialogue between religions, when religions separated entire worlds from one another, literature, as the ideology-free art of pure storytelling, was the main domain where thoughts could be exchanged. These stories of love and adventure, heroism or sainthood, brazenness or devotion, of saints, invaders or martyrs would get combined, augmented, abridged; names and places in those stories would mix, time and space, truth and fiction would lose ethnic or religious belonging and would shape into a separate reality. That’s why it is almost impossible today to trace the origin of this or that literary work, whether it is Greek or Persian, Arabic or Jewish, Armenian or Georgian, Turkish or Kurdish, because they used to originate in the most hybrid environments and spread through entire regions at lightning speed. Hence, if there is anything that can overcome nationalistic and chauvinistic impulses today, it is precisely the Middle Ages, the research into it and the knowledge of this epoch.

Georgia and its literature were also an organic part of that shared space. Stories, either heard or read, were internalized and adapted by Georgians, so much so that the genesis of those stories were soon forgotten. An example of such borrowing was a popular story, later called “Aleksandriani” - a Georgian adaptation of exploits of Alexander the Great. After the author known as Pseudo-Callisthenes wrote the “Alexander Romance,” the story of this invader went beyond the boundaries of its author and that historical king and made it into oral literature. Since then, images of Alexander as a pagan, Christian or Islamic king could be found in various folklores. Georgians adopted the image of this pagan, Cristian and Islamic king too, embedding it in their literary and historical heritage as it can be seen in historical texts such as “The Conversion of Kartli” or “The Georgian Chronicles.” Authors of Georgian chronicles turned the great Macedonian king into part of their history and virtually, into the founder of Kartli. In the 11th century, the “Alexander Romance” was even rendered in Georgian, though it did not survive to our times.

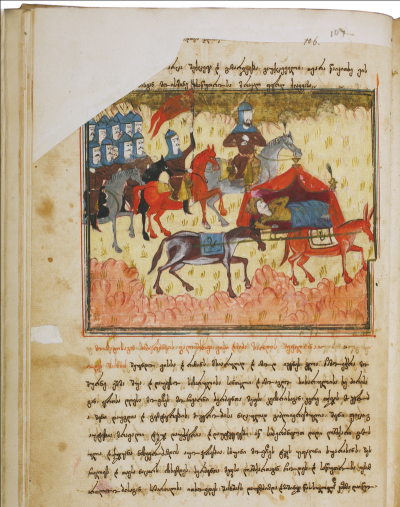

By the time of adopting Christianity, the Georgian, and generally, Caucasian culture was of hybrid nature. The newly introduced faith and ideology was slowly but surely gaining a foothold on the old Zoroastrian land. The following centuries represented the period of syncretism, synthesis or fight of these two religions. If we read “The Georgian Chronicles” attentively, beyond its deeply Christian nature we will discern old Iranian images and symbols and the influence of the tradition of Iranian epic – “Shahnameh.” Thus, a significant monument of medieval Georgian literature, “The Georgian Chronicles,” which is the history of Christianity of Georgia, at the same time shows the influence of Iranian tradition. The alteration of Persian (first Iranian-Zoroastrian and then Muslim) form and Christian (Byzantine, Georgian) content became a key trait of Georgian culture and especially, literature of the following centuries.

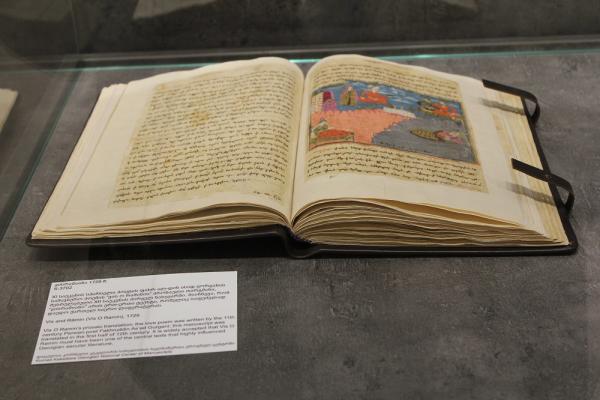

This hybridism and diversity became most conspicuous in Georgia from the start of the second millennium. That time saw the emergence of something we now call a secular literature. This literature is secular inasmuch as it brings together and mixes Persian, Arabic, Greek and Georgian folk motives in terms of form as well as content. The most outstanding example of such work is the text that reached our times under the title of “Balavariani.”

In the 9th century, Georgian monks living in Palestine translated a strange text, “The Story of Barlaam and Josaphat,” from Arabic. It was partly hagiography but to a greater extent, an epic. In reality, the origin of the story was neither Christian nor epic but it was the story of Gautama Buddha, the legendary founder of Buddhism. Owing to a strange medieval trajectory that this story passed through Arabic into Georgian. Georgians translated it from Arabic and transformed it into a Christian tale. In the 11th century, Euthymius the Athonite, the leader of the Georgian monastery on Mount Athos, translated this Georgianized story into Greek, Christianizing it further and adjusting it to the requirements of hagiographic genre of those times. It was that Christianized version of the story that spread across Europe and became one of most famous and popular writings of the Middle Ages. Georgian and Greek texts of “Balavariani” differ rather starkly and this difference lies precisely in diversity – while the Greek version is adapted to rules of hagiography and Christianity, the Georgian original of the text is cosmopolitan, focused on stories and parables. That very secular language, style and cosmopolitan identity of “Balavariani” laid the foundation for secular literature in Georgia – the literature that had no analogue at that time and in that space and that made the creation of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” possible.

“Balavariani” was followed by the major texts of Georgian literature, such as “Visramiani,” “Amiran-Darejaniani” and then, “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.” Apart from the texts having reached our times, we know that there were Georgian versions of Persian “Shahnameh,” a lost epic about the hero Dilargeti, and many other literary creations that were either conceived and created in Georgia, like The Knight in the Panther’s Skin, or travelled a long way through time and space before they were Georgianized, like “Visramiani.” None of these works could be attributed to any one of the cultures, faiths and ideologies. None of the authors of those writings were interested in national identity, ethnic problems or religious casuistry, but only in what was universal, eternal and common for all – love, devotion, friendship and other human virtues.

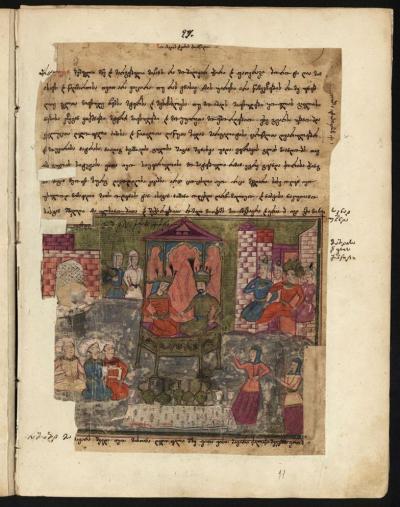

By the early 12th century, two seemingly independent but interlinked processes achieved the peak simultaneously in Georgia. By that time, Georgian enlightened monks had already inhabited Byzantine monastic centers and uninterruptedly translated newest literature of that time from Greek. The Georgian Iviron monastery had been founded on Mount Athos and Euthymius the Athonite and George the Hagiorite translated virtually everything that was written and read in Byzantine of that time, thus laying the foundation for new Georgian literature. Thereafter, Ephrem Mtsire, Arsen of Iqalto, Ioane Petritsi and others gave birth to, developed and refined Hellenophilism which pursued the objective of aligning the Georgian literature with the then modern Byzantine tendencies – a process that started with Gregory of Khandzta in the 9th century and reached its peak in Gelati in the 13th century.

However, this process of Byzantination was selective from the very start. While Byzantining their culture, Georgians were also enriching it with neighboring Muslim cultures. In 1122, David the Builder liberated Tbilisi and after the interval of four centuries, it became the capital of the Georgian kingdom. Both the capital and the throne moved from Kutaisi to Tbilisi. In contrast to monoethnic and mono-religious Kutaisi, Tbilisi was a genuinely cosmopolitan city bringing together traders, citizens, poets of all nationalities. Tbilisi and its suburbs were visited by poets, ashugs and gusans (folk poet-musicians) travelling from all over the Caucasus, South West Asia and Near East, bringing with them dastans, i.e. stories in the forms of verse and song. Georgians, be they kings, nobles or commoners, were passionate about that new and strange phenomenon and keen to internalize it. It was precisely that Tbilisian ashug tradition that centuries later culminated in a mixed Armenian-Azerbaijani-Persian-Georgian poetry of Sayat-Nova as a symbol of Transcaucasian diversity.

That hybridism and diversity influenced daily life and especially, language. While Ioane Petritsi and monks at Gelati were creating scientific language, enriching the Georgian conceptual apparatus with Greek vocabulary, the Georgian language was simultaneously adopting Persian vocabulary. Proper names of Georgians were dominated by names of characters from Iranian epics, especially from the “Shahnameh.”

Having moved to Tbilisi, the Georgian literary and political elite cemented its ties with neighboring Shirvan, one of culturally most advanced Muslim states. From Shirvan Georgians adopted a type of literature that had a profound influence on the Georgian literature. Through closeness to Shirvan Georgians discovered a love story of “Vīs and Rāmīn,” an epic which was composed in poetry by Fakhruddin Gorgani in the 11th century, and learned about a great Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi who, along with Shota Rustaveli, is a symbol of Transcaucasian literature of that epoch. These literary ties experienced such a refinement over time that the Georgian version of “Visramiani” has been recognized a masterpiece of Georgian prose.

Therefore, although a famous quote from The Knight in the Panther’s Skin: “to us men He has given the world, infinite in variety we possess it” does not imply the diversity in the modern understanding of the notion, Rustaveli maintains a constant dialogue with different and distant cultures, ideas and philosophers. Rustaveli is familiar with Ferdowsi’s “Shahnameh” where Rostam, like Tariel, is clad in panther’s skin. Rustaveli indirectly criticizes two popular love stories of those times - Vis and Ramin and Nizami Ganjavi’s” Layla and Majnun.” Rustaveli is also familiar with a love story of Vamek and Ezra and “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” is full of such exchanges with classical as well as his contemporary Byzantine, Arabic and Persian literature.

Diversity is seen even in the language of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.” A term borrowed from Greek philosophy, a word derived from the Mongolian root, a quote from a work of Persian literature may all be found side by side just in one paragraph. Rustaveli uses various words for poetry or poet, which have roots in Arabic and Greek. The God for Rustaveli is also a Platonic “one”, unarticulated and strange which is synonymous to love and romance, the “one” that is common for Platonists of all religions both in the West and East.

However, one may wonder what happened in the 11th century Georgia that triggered a process which had no analogue in terms of diversity either before or after that brief period in history. From the 11th century Georgia saw a period of great revival, both political and cultural. That revival reached its peak in the early 13th century. In that period Georgians were fully aware of their political and cultural strength and dignity; they did not suffer from a complex of occupied and oppressed people, or to put it in modern parlance, a postcolonial complex. They were not afraid of the strange or a stranger, did not reject foreign culture for fears that it would undermine their own identity or someone would deprive them of their Georgian origin. It was precisely such people that readily assimilated Iranian and Arab, Turkish and Greek, Armenian and North Caucasian cultures. As Donald Rayfield noted correctly, such receptiveness of foreign and different cultures was only possible for Georgia that enjoyed the peak of its strength: the confidence of a newly united Georgian state enabled it to wholeheartedly embrace foreign literature and to adopt values of the culture that represented a mortal danger to Georgians for over a century. All monuments of literature, mentioned above, and a crowning work of Georgian literature, “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin,” were created in a free and diverse Georgia of that kind and not by the nation that was culturally isolated and obsessed with fear about its identity.

This article was made possible by the generous support of the American People through The United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The content of this article is the responsibility of TDI and the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of East West Management Institute, USAID or United States Government.

The project is implemented by the Tolerance and Diversity Institute within the framework of USAUD program, Promoting Rule of Law in Georgia (PROLoG), carried out by the East-West Management Institute (EWMI).